Cycling there and back again

As I watch the remarkable athletes bike around the course in Hamilton, this mediocre athlete will enjoy a moment of private satisfaction, knowing that I’ve done something these top cyclists have yet to attempt.

As a boy, I dreamed of winning a bushel of gold medals at several Olympics. But I arrived at 50, no gold medals to my name; I never fulfilled my athletic dream.

At 50, my un-optioned screenplays gathering dust, my pitch to the World Bank for eco-development in Africa dying on the competition short-list, I asked myself what is an enterprising baby boomer with no money, but a desire larger than his talents, to do?

The answer was called Tour d’Afrique, a bicycle journey almost 11,000 kilometres long. And it had never been done before. The idea was born when the frustrated athlete shared a car ride in the magnificent mountains of Ethiopia with a former Canadian Olympian; we were watching the Russian cycling team training for the Olympics. “What if . . .?” I asked. Yes, it was an incredible long shot, but what if we created the toughest, longest, most exotic bicycle race in the world, crossing Africa from Cairo to Cape Town in 100 days of biking. Thus, after a restless 50th birthday night, I placed a call to a much younger friend who shared my madness for bikes and my anti-car philosophy: “Mike, it is now or never!”

We had discussed the idea a decade earlier. He had even taken a yellow marker and drawn the route on the Michelin map of Africa. Now, it was time to act. With an e-mail to The Guinness Book of World Records — to inquire whether they would recognize a new record for the fastest human-powered crossing of Africa — we were off.

There were only two problems — no money and no participants. The Globe And Mail came to the rescue. A story about our plans (with a map) was published, and dozens of e-mails from as far away as Australia and Japan followed. Most were encouraging. Some signed up immediately, others thought we were either out of our minds or “con men trying to extract money from the gullible.” We were warned about non-existent roads and difficult border crossings. A letter to the editor from an old African hand suggested that “we better not forget to take bulletproof vests and army helmets.” A more official letter from Canadian External Affairs asked us to reconsider, “due to political and security considerations.”

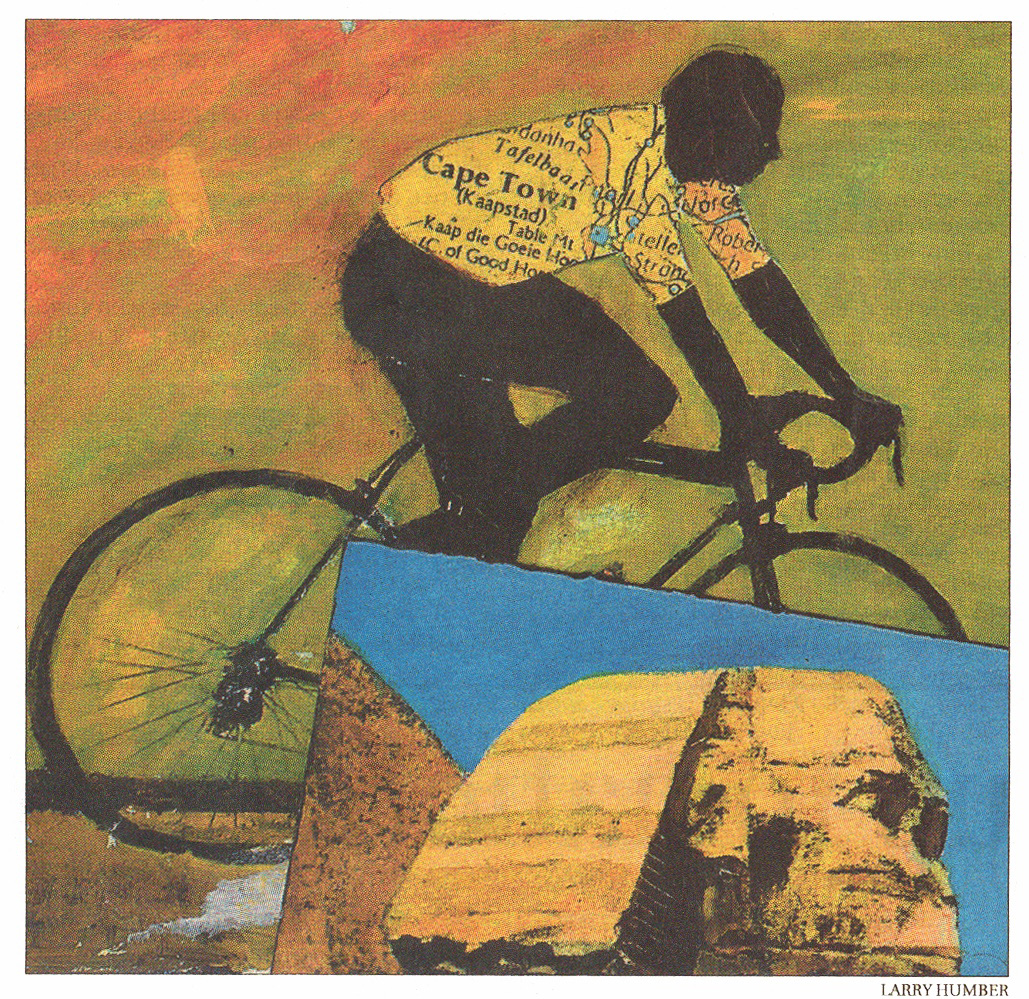

But one does not enter history books by kowtowing to naysayers. On Jan. 18, 2003, three weeks short of my 51st birthday, 33 individuals from eight western countries stood in front of the Great Pyramid at Giza, under the gaze of the immortal Sphinx and the lights of Egyptian television . One by one, we passed under the makeshift start gate, attempting to cycle into history. Collectively, we ranged in age from 21 to 63 — mostly male but several determined females as well, athletic and non-athletic. Among the latter was Sandra Macmillan, a 54-year-old PEI real estate agent and mother of five, who bought a bicycle after reading the original Globe story. She would later confide that she had never ridden a bike in traffic; there in Cairo, she was navigating through one of the most frenzied cities in the world.

The journey took 120 days as planned, 100 days of biking and 20 days of visiting the sights. We travelled through deserts and savannahs, in searing heat and driving rain, on good roads and non-existent paths.

While the rest of the world was preoccupied with the Iraq crisis, we calmly pedalled from one country to another. No, it was not easy — quite the opposite. The night before we arrived in Nairobi — our symbolic half-way point — Fred Promoli, a mountain of a man, a former Canadian Navy diver, veteran of the famed Montreal-Ottawa ski marathon and an educator, organized an Indian circle. Fred set the tone when he broke into tears describing the difficulties we had faced making it that far. Others followed. Greg Wells, armed with a new PhD in sports physiology from the University of Toronto, recounted his experience working with Olympic athletes. “Believe me, this is tougher than anything they go through.” Scotty Robinson, a Toronto spin instructor, also broke into tears, and later wrote to his sponsor: “I have never been more tired, more disgustingly dirty and more happy, calm and exhilarated on any bike ride in my life. This must be euphoria and I’m hooked. What a ride! It’s great to be alive!” The race was won by Sasha Hartl, 26, an Austrian and a vegetarian to boot; he covered the 10,957 km. in 430 hours, 22 minutes. Of the 33 riders who started the trip, 31 managed to finish, hugging each other on Cape Town beach with majestic Table Mountain in the background. We had done what few thought was possible. We had conquered the Mount Everest of biking. We had set the bar higher.

I did not finish in the medals. Nor did I even try. After all, at 51, a man has lived long enough to acquire a little wisdom. A couple of others and I — we called ourselves the “back pack” — spent a not insignificant amount of time each day visiting local tea shops, beer hangouts and chatting with the locals, or just resting and enjoying the scenery. But each day, whether we had to climb the mountains of Ethiopia or push the bike through the sand of a Sudanese desert, we arrived in camp tired but exhilarated, completing our personal quest.

So this weekend, at the Road World Cycling Championships in Hamilton, I’ll be distributing leaflets for the second running of Tour D’Afrique, which starts Jan.17 , 2004, and feeling like a man whose impossible dream came true. Call it pride. Call it arrogance, if you like. But as I watch these remarkable athletes bike around the course, this mediocre athlete will enjoy a moment of private satisfaction, knowing that I’ve done something these top cyclists have yet to attempt.

Henry Gold lives in Toronto.

Published by The Globe and Mail October 9, 2003

2003-01-18 10 967 2003-05-18 Sascha Hartl,

Austria Marie-Claude Baehler,

Switzerland Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania,

Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana, South Africa

<< B i c i t u d i n e | Sweet and Low >>