Random Bikes - Musette Caffè

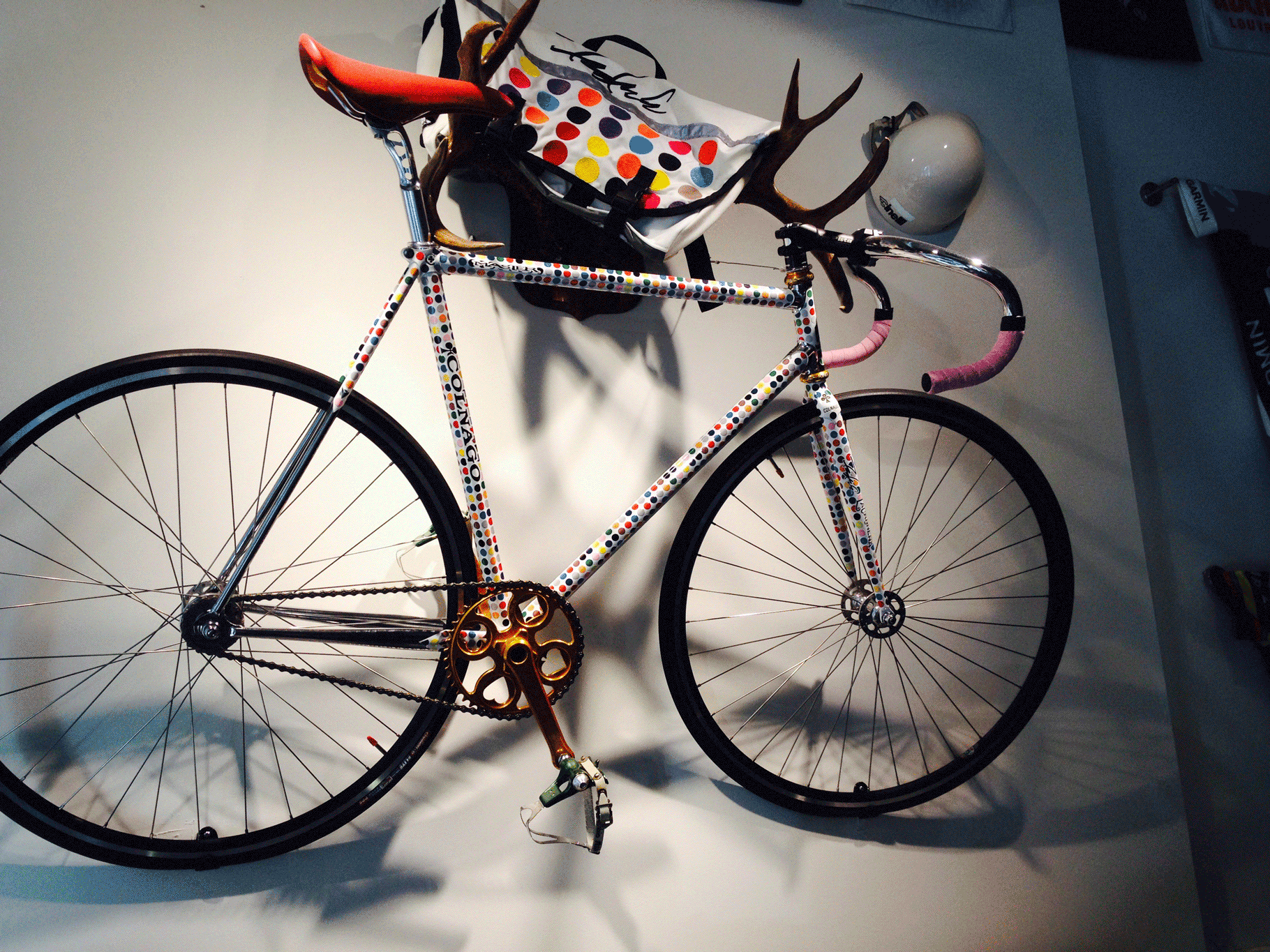

Snapped this photo at the Musette Caffè, located on Pender Street in chinatown, which is no longer in business having closed shop. Looks to be a classic Colonago Master Pista bike. No news of the bikes’s current location.

Musette Caffè is a bike-friendly, licensed Caffe.

@giordanacycling

Random Bikes - Cologne

This looks like it could be an ideal rental city bike.

Saw it in Cologne: Call a Bike

Paul Sherwen

Cycling broadcaster and former professional rider Paul Sherwen has passed away at 62-years-old. The Lancashire, England native was the voice of the Tour de France for many viewers commentating alongside Phil Ligget for decades most recently on NBC Sports. Sherwen lived in Kampala, Uganda.

Before becoming a broadcaster, Sherwen was a professional cyclist racing the Tour de France on seven occasions between 1978 and 1985. He was British national champion twice during his career.

Ci Distinguiamo

Solo tu fai al CAOS mio

Giulia Frosi

Bicycle Graphic Design

Well this site contains a few cycling graphics that should please every cycling fan.

Source

Why Bicycles Don't Tip

“Simple Explanation Of The Principles Of Balanced Involved

Riding That Is Easy and Riding That Is Difficult – The Steering of the Wheel from Side to Side Keeps It Under the Centre of Gravity of the Body – What Speed Has to Do With it – Facts of Interest to All Wheelmen.”“ When bicycles first came into use, the general impression was that the task of balancing them could only be acquired after weeks of patient and persevering practice. This is not true; nevertheless, it would not be reasonable to form any other conclusion if guided wholly by appearance, for certainly when one sees a rider coming along the road, the wonder is, how can he manage to keep in an upright position with so little apparent effort. It is probable that there are very few persons who have not at some time or other tried to settle in their own minds this question, and, judging from the general impression that prevails among those who do not know how to ride, the conclusions arrived at are in most cases erroneous. Almost every one believes that it is easier to balance the wheel when running slow than when going at a high rate of speed, but this is just the reverse of the facts, as every rider well knows. The most difficult thing to do on a bicycle is to stand still. The next most difficult thing is to move along at the slowest possible speed. Any novice can ride at a ten or twelve mile per hour velocity, but he who can go at one mile rate is an expert.

As a matter of fact, the art of balancing a bicycle is not difficult to acquire, and now when nearly every one rides this fact has become very well known. Why a feat that looks so difficult should be so easy has puzzled many a mind, and any number of attempts to solve the problem have been made, but in almost every case the theories developed have been incorrect, either wholly or in part. The most common notion that prevails in relation to the subject is that the headway, as it is generally expressed, or, more properly speaking, the momentum, keeps the wheel from falling over. This supposition is only partially true; the velocity only assists in maintaining a balance, and this is the reason why it is easier to ride fast than slow. But this very fact, that speed simplifies the act of balancing, has led almost every one to believe that it is the only cause upon which the action depends.

The real reason why a bicycle can be balanced so easily is that the wheel can be steered from side to side; and thus be kept under the centre of gravity of the body. If the wheel could not be turned to one side or the other, but was confined to a straight line, the balance could only be maintained by throwing the body from side to side, so as to keep the centre of gravity over the wheel, and this would be far more difficult to accomplish. To illustrate this point, consider the case of a man trying to balance himself upon the heels of his shoes. He will soon feel that his weight is going either forward or back-ward, and to avoid falling over he will take a few short steps in the direction in which his body is moving, and thus restore the equilibrium. So long as he keeps moving his heels, one way or the other, he will have no difficulty In preserving his balance; but if he tries to accomplish the same result without moving his heels he will find that he can only maintain a balance for a few seconds, and to accompliRh even that much he will have to swing his body and arms around in anything but a graceful manner. This explains why it is so much easier to maintain a balance on stilts than on a tight rope. One would naturally suppose that the latter would be the easier, because the whole length of the foot rests upon the rope, and, therefore, only the tendency to fall over sidewise has to be counteracted; while with the stilts, as they terminate in very small ends, the body can tip in any direction. But the stilt walker can balance himself without difficulty, because no matter in what direction he may incline he can keep the stilts under the body by simply stepping in that direction. >>eXc

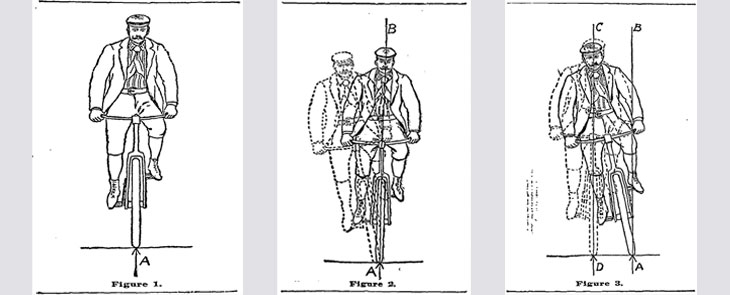

How these principles apply to the act of balancing a bicycle can be readily explained by the aid of the accompanying figures.

Suppose the rider, shown in Figure 1, is required to keep the wheel on the straight line A. It is evident, then, that when he begins to incline to one side, as shown by the dotted lines in Figure 2, he can only restore the balance by throwing the body in the opposite direction; and that he must throw it far enough beyond the upright line A B to equalize the weight on both sides. This at once shows that if he should allow himself to tip over as far as shown in the figure, he could not regain an equilibrium; as it would be impossible to throw the body far enough in the the opposite direction for that purpose. This fact alone shows that it would be necessary to act with great promptness, and endeavour to restore the balance just as soon as the inclination to one side became noticeable. In the effort to regain the balance by throwing the body toward the opposite side to that to which the wheel was tipping, it would be more than probable that the weight would be thrown too far, and this would render necessary a quick movement in the contrary direction. The effect of all this would be that the graceful motion of bicycle riders would be converted into a series of contortions that would resemble the performance of a professional india rubber man. And even with all these ungainly movements the balance could not be maintained for more than a few seconds, except by one who had acquired the art by long practice. The most difficult thing a bicycle rider can do, outside of trick riding, is to ride a chalk line. If any one doubts this let him try to follow a wagon wheel track, and he will very soon realize that it is not an easy thing to do.

From the foregoing we can see that the speed of the bicycle will not keep it from tipping over if the wheel is kept on a straight line. The speed prevents it from falling over as easily as it would if standing still, and that is all it does do. The action of the speed is to cause the wheel to tip over more slowly. This gives the rider more of a chance to keep in balance, but if the wheel is not turned from the straight line the equilibrium must be maintained by throwing the weight of the body to one side or the other, and to do this in a graceful and successful manner would require an amount of skill that could only be acquired after long practice.

In the actual riding of a bicycle the balance is maintained by turning the wheel from side to side. This can be easily understood by reference to Figure 3, in which the rider is shown inclined to the same angle as is shown by the dotted outline in Figure 2. By turning the front wheel so as to steer slightly in the same direction in which the body inclines, the position shown by the dotted lines Is soon attained. In this position the wheel is on the line C D, which is directly under the body, To balance in this way it is not necessary to move the body at all, because the result is accomplished by steering the wheel so as to keep it under the centre of gravity, while in the former case the centre of gravity had to be kept over the wheel, and this could only be accomplished by throwing the weight of the body from side to side.

When a rider begins to lean to one side the turning of the wheel in the same direction does not check his side motion. He continues to fall over, but he steers the wheel so that it moves sidewise faster than his body does, and the result is that it very soon reaches a point when it is under the centre of gravity. If a close observation of the movement of a bicyclist could be made it would be found that the upper Part of the body moves along in a line that sways from one side to the other to a slight extent, and that the path of the wheel upon the ground follows the same curve motion, but goes further toward each side than the upper part of the body, The reason for this is that when the body begins to tip to one side the wheel must be steered in the same direction, not only until it runs directly under the centre of gravity, but enough further to check the side swing which the body has acquired in the act of tipping. If the wheel does not run far enough out of line to check the side swing the balance could not be restored.

While the actual balancing is effected by deviating the course of the wheel from side to side, the headway assists, as already stated, in maintaining the equilibrium. The reason for this is that the momentum when the wheel is in motion acts against the force of gravity, and consequently the net force that tends to push the weight to the ground is less. This causes it to drop more slowly and gives the rider more time in which to regain his balance. To illustrate this more clearly, suppose we consider an ordinary boy’s hoop. if you try to balance it while standing still you will find It to be impossible. As soon as it is released it will begin to fall, and will strike the ground flat on its side in short order. If, instead of trying to balance the hoop standing still, you roll it along, the action will be very different. At first the hoop will roll in a straight line, but almost immediately it will begin to follow a curved path, which will grow smaller and smaller until finally it will course around in an apparently circular path, which will diminish in size as the headway dies out. The explanation of this action is that just as soon as the hoop gets out of balance the force of gravity begins to draw the heavy side down to the ground, just as it would if the hoop were not in motion. But the momentum of the hoop, acquired on account of its velocity, tends to keep it moving in a straight line; therefore, there are two forces acting against each other, and the result is that the hoop leans over and begins to run in a curved path. This curve grows smaller, because the force of gravity remains unchanged, while the momentum gradually dies out; consequently as the former slowly gains the mastery over the latter the weight is drawn nearer and nearer to the ground. The curve in which the hoop rolls becomes smaller and smaller, because the angle at which it inclines increases as the headway dies out. Therefore, the part that comes in contact with the ground keeps shifting away from the periphery, which would trace a straight line, to the side, which would trace a circle equal to the diameter of the hoop. The path of the hoop, therefore, begins with a straight line and then turns into a spiral, which grows smaller with each turn, and finally ends in a circle not much larger than the hoop itself. Any one who is at all observing can notice that the time required for the hoop that is rolled along to drop is much longer than that for the one that is allowed to fall over while standing still. The difference in the time in the two cases will depend wholly upon the velocity, If the hoop is rolled off very gently it will drop on its side very soon, but if it is given a good start it will run around for some time. This is simply because in the latter case the headway is much greater, and as this counteracts the effect of the force of gravity, the latter cannot succeed in drawing the hoop down to the ground until the force of the headway has died out.

What is true of a hoop is true of a bicycle, and as ‘a high velocity keeps the former upright for a greater length of time than a slow motion, so it does the latter. This Is the reason why it is easier to keep a wheel in balance when moving fast than when running slow.

At a sufficiently high velocity a bicycle could be kept In the upright position for a considerable length of time without making any effort to balance it by steering the wheel sideways, but at a slow speed this could not be done. One of the most difficult feats of balancing that can be done on a wheel is to keep it upright while standing still, with both wheels in line.

Those who have seen professional trick riders must have noticed that whenever they perform on a bicycle that is not in motion, the front wheel is not in line with the hind one, but is turned at a considerable angle. This greatly simplifies the act of balancing. It helps In two ways; one is that when the front wheel is turned around at an angle it increases the width of the base upon which the bicycle rests, for the simple reason that the length of ground covered by the wheel lengthwise is much more than sidewise. The principal advantage of turning the wheel around, however, is that when in that position it can be rolled back and forth slightly as occasion may require to maintain the balance. If the rider feels that he is beginning to tip over to the right, a very slight pressure on one of the pedals will move the wheels sufficiently to send the front one far enough to the right to check the tipping-over tendency. If the weight inclines to the left, a small movement of the corresponding pedal will restore the equilibrium. In this way the bicycle can be kept balanced for a long time without any apparent effort but a close observer will notice that the wheels are continually moving either in one direction or the other.

Published: July 5, 1896 Copyright© The New York Times

Chasing Annie

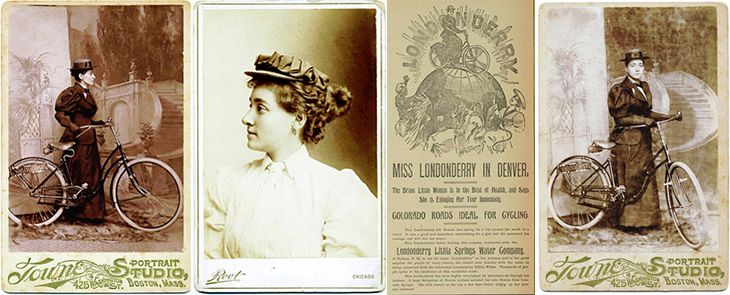

One Monday in late June 1894, a slight, unprepossessing woman in her early 20s climbed onto a Columbia bicycle in front of the Massachusetts State House in Boston. Annie Cohen Kopchovsky was 5- foot-3, about 100 pounds. Aside from two quick lessons in the previous days she had never ridden a bicycle in her life. All across the country, women who’d never balanced atop two wheels were taking to bicycles, but not merely for recreation or transport. Women used bikes as vehicles of political and social change, too. The women’s suffrage movement and the cycling craze went hand in hand. On two wheels, women found independence and freedom of movement. Because pedaling in billowing Victorian skirts and corsets was impractical, for instance, female cyclists popularized bloomers. To critics, these changes symbolized moral corruption.

Frances Willard, one of the most famous women of the times, was a leading suffragist and president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, then the largest women’s political organization. She learned to ride at 53, and mastery of the bicycle as a metaphor for women’s mastery over their lives was the message of her 1895 book, A Wheel Within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle (reprinted in 1997 by Applewood Books). She wrote that she rode “from a love of acquiring this new implement of power and literally putting it underfoot.” Indeed, fellow suffragist Susan B. Anthony said in 1896 that the bicycle “has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.”

From Peter Zheutlin’s article in Bicycling magazine:

Source

China Creek Cycle Track

“Michael Cooper”

Michael Cooper posted this photo on Facebook with the caption:“This is the sprint final for a race on the China Creek Cycling Track, probably in 1976 or 1977. That is the Washington State sprint champion Richard Snavely on the bottom, me leading at the top of the banking and Ed McRae behind me. The track was torn down in 1980. Our last full racing season was 1979. I was the last BC Track Champion on this track.”

Claude Dube

They Yapped All Day

Claude Dube, the 28-year-oId Quebec cyclist who left Montreal last summer bound for Osaka 70 with a caravan of 90 girls, is back in Montreal – $20,000 in the red.

And he never did make it to Japan.

“When we got lo Vancouver they told me they didn’t need me anymore,” he told The Gazette yesterday.

‘The girls left me with all the debts and humiliated – but it was an experience.” Dube became. a well-known figure in 1966 when he peddled from Vancouver to Montreal and in Centennial year he led a group of young girls on a bicycle caravan from Halifax lo Expo 67.

He has written a book entitled Around the World in 6o Months on a Bicycle With $5.

His Montreal – Vancouver- Osaka caravan was to have arrived in Japan for the opening of Expo ’70

But he said he made four mistakes:

“I accepted too many unilingual French-Canadians,” he said. “It made communication next to impossible as i had to repeat everything twice, once in English then in French.”

“1 accepted too many minors ,” he continued. “Sometimes l almost bad lo fight to get them out of bars.

“Thirdly, I had loo much confidence in women, l’ve learned my lesson now.”

“And my fourth mistake was to head for the bottle to calm my nerves,” he said.

“From the time we left Montreal lo the time wc got to Vancouver, all they did is yap all day,” be said.

When the troupe finally arrived in Vancouver, last

Oct. 17. after four months of cycling across Canada, six girls 1eft the caravan.

There the six girls met public relations officers and became involved in various fund raising campaigns, Dube said.

They told the rest of the. girls that a lot of money could be made and the best way to do it would he to leave Dube and form an all girl caravan, he said. “And that is what they did.

“Eventually the publicity deals fell through and 30 girls are still stranded in Vancouver,” Dube said. “I was left with all the tents, bicycles and equipment.”

He said he sold everything but his 1951 car and returned to Montrea1.

“But I haven’t given up on cycling.” he said yesterday. “l’m trying to organize a two-month trip around the province this summer.

“But this time it won’t be all women – no sir.”

By Richard Nutbrown The Montreal Gazette – Mar 27, 1970 source

NFB movie: 10 milles/heure

10 milles/heure by Marcel Carrière, National Film Board of Canada